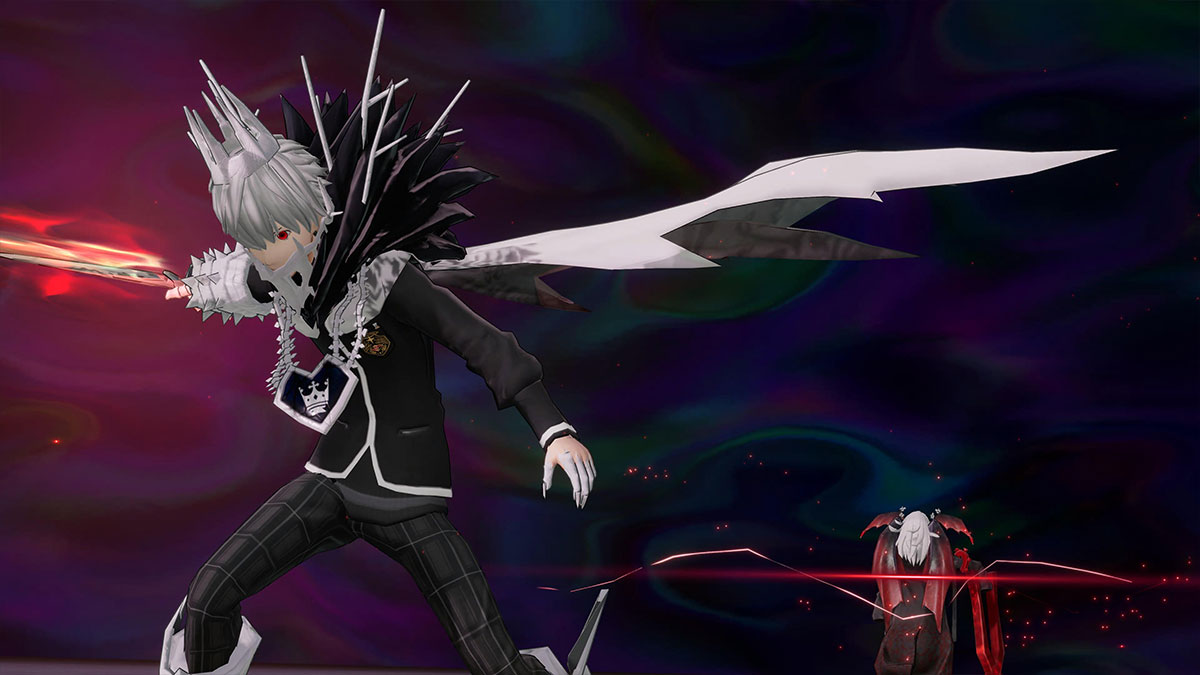

Monark is caught between worlds of play. At once, it feels like a follow-up to massive, genre-defining hits like Persona 5 and a plucky smaller-budget JRPG inspired by modern classics. Its distinctive, anime gothic key art languishes in the cel-shade of its more conventional 3D models. Its unique take on tactical RPG combat gets tiresome and empty over dozens of hours. Its characters are anime stock, only given subversion in flickers and whispers. Monark constantly strains within the confines of expectation, unable to push its ambitions through.

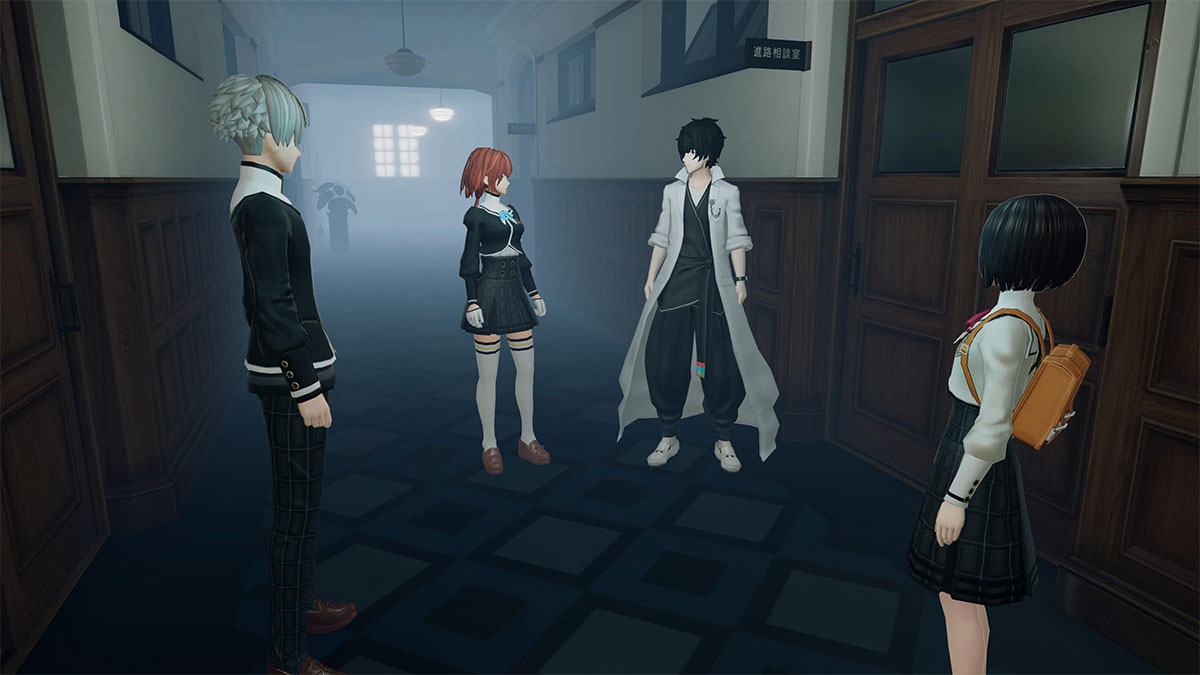

The game opens with a cutscene depicting regular life at the secretive Shin Mikado Academy. Quickly, everything goes to hell. A strange magic barrier seals the school off from the rest of the world. A maddening mist descends over much of the academy. This chaos is the result of pact bearers, regular human beings who seal promises with Daemons from the Otherworld. These Monarks, each represented by one of the seven deadly sins, grant obscene power in exchange for the distortion of the world.

Rescued by his little sister Chiyo, the player-named protagonist finds that he too is a pact-bearer. Instead of one of the deadly sins, he is bound to the mysterious entity Vanitas. This makes him an enemy of the academy, but also potentially its greatest asset. His powers enable him to combat the pact bearers haunting the campus. With this in mind, the dean recruits the protagonist as part of the “true student council,” and tasks him with defeating the villainous pact bearers. As he proceeds on his mission, the dean’s motivations, and the school’s true nature, are drawn into question.

Zombie high

Self evidently, Monark pulls from a long history of Japanese school-based horror media such as The Drifting Classroom and Corpse Party. This inspiration is set-dressing. The supernatural occurrences of the school are quickly explained in a flurry of proper nouns and game systems. Monark’s remaining mysteries are plotty rather than evocative. The sudden disruption of normalcy and the recontextualizing of suddenly fraught relationships can make for terrifying and heartfelt horror. Instead, Monark sweeps that aside for a focus on the lore of its haunting setting.

In other horror influences, Monark does incorporate a kind of digital horror aesthetic. Receiving cell phone calls is the primary means of traveling between the otherworld and the school. When transported to the otherworld, the screen flickers with blocky pixels. This invocation is also underdeveloped. The game doesn’t really have anything to say about digital, haunted space — it is instead a flicker of style, for its purely practical interfaces.

This empty aesthetic is a central part of the game’s puzzles. Each “dungeon” only has one or two proper battles. The “play” of the dungeon is about discovering information. You find the codes for locked doors or convince hiding students to let you in by scouring your phone and school campus for the right words or secrets. It’s easy to extrapolate this to digital invasion of privacy, but the game never goes there. Instead, the horror of digital knowledge is just a fact of navigating Shin Mikado. The puzzles themselves are ponderous, often requiring multiple, difficult-to-find cross-references. Alongside my notes for this review are dozens of little notes of phone numbers, dates, and codes to help me solve puzzles. Some are undoubtedly brain teasers, but just as often they are trivial or obscure. They always take too much time.

A world where time has stopped

That ponderousness is unfortunately a pattern. I undoubtedly felt this more because I was under a deadline, but everything in Monark takes forever. Characters repeat barely differing theses back at each other in lengthy cutscenes. Battles don’t only grow in difficulty, but stretch out in space and time, involving more enemies who take more hits over a larger area. Since Monark relies on the same set of units, on discreet battles without any interconnection, it pushes you through similar battlegrounds and enemies. The simple joy of grinding, often a means of expressing a setting’s particular character, is a purely repetitive slog. It pushes you through the mud of the same battles in the same areas, over and over again.

However, fighting still has its share of virtues. Monark stands in a middle ground between classic tactics RPGs and the regular turn-based fair. Battles take place on a 2D plane, filled with obstacles like destructible walls and poison plants. Every attack has a specific range. Some will hit any enemy you can place in a cone shape or wallop a specific enemy within a circular radius. Depending on their patron sin, each unit has unique abilities. Some have devastating elemental attacks, others can manipulate the stats of both friends and foes. The protagonist’s central ability, resonance, lets him chain status effects between units, friendly or not. At its best, Monark forces you to grant stat buffs and then chain them between friendly units for maximum damage. I found it a bit difficult to wrap my head around, as I’m more used to classic JRPG combat and am notoriously bad at tactics games. Nevertheless, I had some thrilling moments chaining powerful attacks between allies and squeezing out victories from desperate situations.

I always thought you were cool

High school stories often rely on hazy regret. All of us watched strangers suffer in adolescence. Then we watched as they faded from memory, becoming Facebook friends or distant acquaintances. At best, they became new friends, someone to celebrate how much better life is now or commiserate that it has only gotten worse. The Stephen King novel Carrie still hits, despite its casual misogyny, because it plays in that regret. We watch as Carrie is relentlessly bullied, as genuine attempts to do right by her fail, while she can do nothing. Except, of course, Carrie has power we cannot imagine. When she unleashes it, no one will forget her. It’s a fantasy, both terrible and beautiful. She murders her corner of the world, because her soul has been killed over and over again.

Monark plays with similar ground, putting quietly suffering teens into contact with horrific power, and watching as their world explodes in blood. However, it lacks the edge of empathy. It renders its horror with a textbook tone. The story gleefully goes to taboo places, but it is ponderously diagnosed instead of shocking. One minor villain’s tragic backstory was so comically shallow and Freudian, I laughed out loud. A game relying on psychological characterization needs more depth than “my father didn’t love me” or “I am jealous of youth.”

This dismissive characterization applies, if less cruelly, to its central cast as well. The central characters are formulas rather than people, condensed to a set routine of potential beats. An overworked and plucky student body president, a withdrawn and socially clueless genius, a rebellious rich kid with a heart of gold, and a sensitive but strong-willed femboy make up the central cast. While all get fleshed out individually, it never feels like they get to move beyond their clichés. At least, not without the help of the blank slate player character.

Mirror, mirror

In each of Monark’s major story sections, only one of the game’s central characters accompanies the protagonist. This means that each of the characters can only build a substantial relationship with a (male) player insert. Interactions between party members are found almost exclusively in the true student council’s home base and are limited to goofs and light banter. Any further relationships between cast members are channeled through you. This makes each character’s social lives feel hollow and empty. Outside of the flickers of backstory, they feel as summoned from the plot as the voiceless protagonist. The game salvages a lot through strong, frequently subtle, voice work. Still, that can only do so much.

Furthermore, when the main character is explicitly a blank slate, it is difficult for the game to frame relationships as interpersonal, rather than possessive. Some of Monark’s most deft characterization comes in convincing each central character to join you in the game’s second act. The protagonist essentially calls them out, pointing honestly to their psychological hang-ups and moving them to action. This does result in some moving material. Ultimately though, it feels like a therapy session more than a conversation between friends. Here, the game forces you through a strange trial and error, churning through a web of dialogue options before discovering the “correct” path. It re-enforces a ludic myth that the right words can make things completely right. It is a very egocentric form of design.

This realization hit hardest through Kokoro, the aforementioned shy genius. Let me be clear: I fucking adore Kokoro. To be frank, I relate to her. Her main desires in life are to be left alone, eat carby foods, and read a lot. Me too, bitch! Her struggle to be understood, and her desire to not hurt others, was the most considered and resonant of the initial stories. After convincing her to join me, I realized that I wasn’t supposed to identify with Kokoro, but rather to claim her, even to fix her. The protagonist offers his love and the promise to always try to understand her, even when it is difficult. This would be a beautiful wish in the hands of a real person. But when Kokoro talks about finally finding someone who would try to understand her, she is not talking about a real human being, but a stoic mirror, forever placed in front of the same plain wall. Her growth comes only through that mirror, she cannot find it with anyone else. This gains an uneasy subtext when one considers Kokoro’s unstated autism. The game never considers that the player could also be neurodivergent. The blank slate’s lack of character permits him to be a perfect standard for normalcy, one who can account for Kokoro’s “deficiencies.”

The devils are queer

Worth examining too is Monark’s background queerphobia. In the aforementioned student logs, one can unlock redacted secrets. One of these logs claims one of the female students is “really a man,” only pretending to be a woman because of their self-obsession. This is garden-variety transphobia. It’s not surprising, but nevertheless off-putting. Especially since the game routinely pushes even subtextual queerness into the margins.

The difference between the protagonist’s relationships with female and male characters is also strongly felt. Kokoro’s story in the second act was romantic, with her wishing aloud for a life spent in joy and sorrow together. The act with the rich rebel Ryotaro lacks even the tender homosocial. Even though the Protagonist shakes up his world view in a similar manner to other arcs, it is more like doing a solid for a middling friend than the life-changing revelation of Kokoro’s newfound relationship. In this way, the game expresses a deep set heteronormativity, a true unwillingness to show men loving each other, even the broadest sense.

The verdict

Many of Monark’s problems come from the standards of what a game like this has to be. Fully articulated cutscenes, 3D models, explosive pre-rendered moments, a few dozen hours of RPG battling, and an elaborate and difficult postgame are all present. None of them feel particularly necessary or engaging. Alternate versions of the game do whisper at the margins. The visual novel-like dialogue art is genuinely subtle, sharp, and delightful, showcasing the characters better than any cutscene, pre-rendered or not. The boss battle themes are a cavalcade of banger pop tracks. The alternate paths show a smaller focused game, pulling from its influences, but never feeling beholden to them.

Show me the multitude of things RPGs can be, freed from the burden of franchise and scale. Pull from vital indie games like Tomorrow Won’t Come for Those Without ______ and Flesh, Blood, and Concrete. Ultimately, Monark smothers itself in the shadow of its influences and its pedigree. Like its protagonists, bound by both school bureaucracy and the wily magic of Daemons, it cannot break free on its own terms.

Final Score:

5.5 / 10

| + | A tried and true premise |

| + | Evocative art with occasionally slamming pop tunes |

| – | Strains at its own ambitions and does not recognize the strength of smallness |

| – | Bland protagonist makes relationships shallow |

| – | Repetitive combat can grate, especially on a deadline |

Gamepur team received a PC code for the purpose of this review.

Published: Feb 22, 2022 10:00 am